Birth Outcomes & Experiences Report

Foreword

It is our privilege to write the foreword for this significant report—a collaborative piece of work each of us is proud to have contributed to as part of Amma Birth Companions’ Expert Advisory Group. Together, we represent not only a collection of professionals, but also advocates who are passionate about creating more just and equitable systems of health for the women of colour and birthing people who need it most.

Within the pages of this report, you will find an exploration of the experiences, challenges, and aspirations of women and birthing people as they navigate the profound journey of childbirth. This birthing outcomes report was created and published as part of Amma’s commitment to promoting justice, equity, and the belief that every individual, regardless of their race, language, ability, gender identity, sexuality, or immigration status, deserves the very best health care.

With this report, Amma hopes to encourage and foster an ongoing conversation about the critical need for equitable healthcare provision for racialised women and birthing individuals. This report aims to inspire and initiate an ongoing discourse to ensure that discussions about equitable care and poor maternal outcomes continue and encompass the experiences of those who sit on the margins of existing health systems. We firmly believe that addressing the multifaceted challenges faced by racialised women and birthing individuals requires sustained, long-term commitment and vigilant effort.

This report is but one chapter in an ongoing narrative, and we invite those who read it to join Amma in the collective effort to create a health system that truly serves and safeguards the interests of all individuals from all walks of life, without exception. We truly believe that we can nurture a future where every individual receives health care that protects their physical and emotional well-being, and affords them the respect and dignity they deserve.

In conclusion, our pursuit of improved maternal and birthing outcomes is deeply interwoven with our commitment to social justice and equity. By prioritising the needs and voices of the most marginalised among us—particularly women of colour, trans people of colour, nonbinary people of colour, refugees, and those seeking asylum—we not only uphold a moral imperative but also embrace a practical strategy for systemic improvement.

Signed,

Dr. Anna Beesley, Maternity, Migration and Asylum in Scotland, Social Anthropology, University of Edinburgh

Dr. Jaime Cidro, Professor of Anthropology & Associate Vice-President, Research and Innovation, University of Winnipeg

Dr. Gwenetta Curry, Reader in Race, Ethnicity, and Health, Edinburgh Migration and Ethnicity Health Research Group, University of Edinburgh

Isioma Okolo, MBChB, MPH, DTM, MRCOG, Specialty Registrar, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

Leah Hazard, Midwife, Author, Activist

Dr. Lucy Lowe, Senior Lecturer, Social & Medical Anthropology, University of Edinburgh

Sarah Shemery, PhD Candidate, Social Work, University of Edinburgh

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to the following individuals and groups who played a pivotal role in the completion of this report. This work would not have been possible without the contributions and support of these individuals and groups.

Board of Trustees

for supporting our efforts to create and share this report. A special thank you to our Trustees with lived experience.

Amma Clients

who generously agreed to share their anonymised data for monitoring purposes, which helped to shape the findings of this report.

Expert Advisory Group

whose invaluable wisdom, knowledge, and guidance have been instrumental in the creation of this report.

Interview Participants

who dedicated their time to sharing their personal stories. Thank you for trusting us with your experiences.

Amma Perinatal Services Team

whose cooperation and assistance in gathering data and ensuring that experiences and observations were meaningfully recorded were instrumental to the success of this research.

Sarah Shemery

whose willingness to share her knowledge and collaborate with us on this report. Sarah's exceptional contribution to this project involved data collection and analysis, writing, and coordination of the Expert Steering Group.

Volunteer Companions

whose dedication to the well-being of our clients and detailed insights have provided us with a unique perspective that helps us better understand the experiences and needs of those we serve.

Authors:

Amanda Purdie, Head of Advocacy & Communications

Sarah Shemery, PhD candidate

Sarah Zadik, Head of Services

Editor:

Ellie Brodie, Grounded Insight

A note about inclusive language

At Amma, we recognise and honour the experiences and rights of all individuals seeking maternity care. This includes women, trans people, and non-binary individuals. Therefore, in our work, we utilise gender inclusive language such as 'birthing person' and 'parent'. The information conveyed in this report is reflective of individuals who identify as women and mothers, so for accuracy, we employ these terms when describing their experiences.

Introduction

This report aims to evidence the inequalities in perinatal care that we have observed. Its purpose is to amplify the often-unheard experiences of refugees, women seeking asylum, and those with insecure immigration statuses who are accessing maternity care. It highlights the disparities our clients experience, including practice issues and discrimination, inadequate interpreter provision, and high rates of intervention.

It is not an evaluation of maternity service provision and is not intended to critique or place blame on individual healthcare workers. It does not capture the examples of good practice that we also observe and aim to share directly with maternity services through established feedback mechanisms.

Our intention is to build on the plethora of existing research and scholarship that highlights disparities in perinatal care. We aspire for this report to contribute to the ongoing discourse around creating a more inclusive maternal care system, which has historically been driven by organisations like MBRRACE-UK, Birthrights, and 5x More, as well as many individual birth workers, healthcare workers, academic researchers, and others who have advocated for a more person-centred and equitable approach to birth.

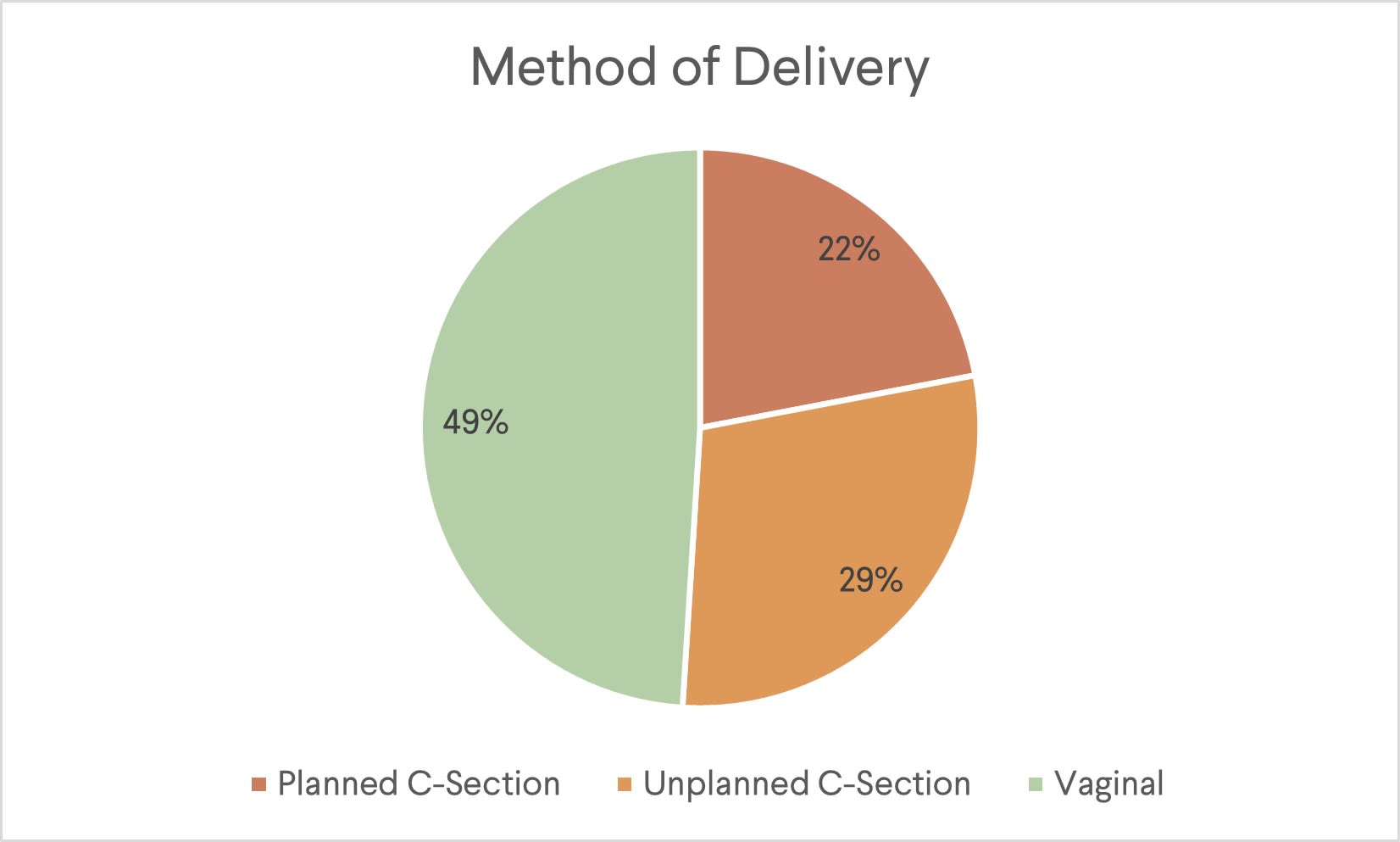

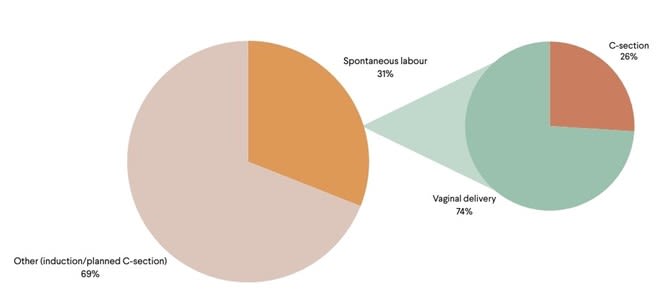

The data presented in this report raises many questions about our clients’ birth experiences, particularly around the lack of choice many individuals have over their births, and how being placed on a high-risk pathway seemingly excludes so many people from a range of options related to childbirth including home births, water births, and midwife-led units.

However, in the words of a former client, "Just because someone is in the asylum system doesn't mean their bodies are broken—or that they lose their ability to give birth".

We believe that how a person chooses to give birth—and whether their choices are honoured—is significant. As this report shows, behind the high rates of inductions and Caesarean sections lie stories of limited options, poor communication, dismissed questions and concerns, and the application of high-risk labels that provoke significant fear and anxiety.

We are concerned that attempts to reduce racialised disparities and lower risk are increasingly focused on interventions like induction as the solution. It is important to balance the offer of interventions against other crucial aspects of care, including the potentially negative impact of inductions on mothers’ and babies’ physical and emotional wellbeing.

We also know that suicide is repeatedly cited as a leading cause of maternal mortality by MBRRACE-UK, particularly amongst women living in deprived areas and those with a history of poor mental health. Research indicates that a negative experience of childbirth has the potential to trigger psychological distress that not only profoundly affects the birthing individual's mental health but also influences their initial interactions with the baby. It is therefore critical that every effort be made to minimise physiological and psychological stress during childbirth.

On top of this, studies show that a poor childbirth experience can have negative effects on the progress of labour, breastfeeding, and bonding, meaning it is vitally important for maternity caregivers to support the positive impact of oxytocin during labour and birth.

Yet, too often, we observe how individuals, already grappling with the stress of the asylum system and coping with histories of trauma, emerge from their childbirth experiences feeling further traumatised and disempowered. We also see women who, in the aftermath of a highly medicalised birth, struggle to physically recover or to confidently establish breastfeeding—especially amongst those with no family or friends to support.

For the clients supported by Amma, the stakes around childbirth are particularly high, as they often lack the interpersonal support, access to resources, and financial means to facilitate an effective recovery from a difficult birth.

Furthermore, it is so important that every individual entering maternity services can access information and make and express choices in their preferred language. This right is fundamental, and we hold a responsibility to ensure its preservation.

It is evident that concerted and collaborative efforts are required to enhance birthing outcomes amongst racialised and minoritised women and birthing people. We are aware of ongoing efforts within Glasgow's maternity services to tackle various issues highlighted in the report, and hope that the insight it provides will be a helpful contribution to these initiatives. We appreciate the willingness of Glasgow's NHS Equalities Team, midwifery services, and the Scottish Government to engage Amma in this work so far and wish for this to continue.

We also acknowledge and deeply sympathise with the challenges of working within a strained and underfunded maternity service, where staff are grappling with burnout. In this context, achieving equity, diversity, and inclusion targets becomes inconsequential without adequate funding and resources to support meaningful and enduring change.

Collaboration with healthcare and government is essential to advocate for improved conditions for both staff and patients. This includes exploring ways to redress the balance between obstetric and midwifery-led models of care— wherein midwives feel adequately supported, empowered to practice the true art of midwifery, and have the time to genuinely listen to individuals' complete narratives. A system that integrates both medical and physiological approaches within a trauma-informed, intersectional, and person-centred framework would contribute significantly to reducing inequalities.

This report outlines several potential solutions that would help to create a more equitable maternal care system—but we do not profess to have all of the answers. This is why we extend an invitation to every reader of this report to join us in the collective endeavour to enact change.

About Amma

Amma Birth Companions is a Scottish charity serving Glasgow. We provide care, information, and advocacy for women and birthing people who are facing birth and parenthood with little to no support. Our clients include individuals seeking asylum, refugees, survivors of human trafficking, gender-based violence, and sexual exploitation, as well as other individuals experiencing multiple inequities.

Since our inception in May 2019, we have provided companionship and community to more than 300 birthing individuals on their journey to parenthood. Our services are focused on three core activities: companionship, peer support, and antenatal education.

Our volunteer companions receive a high level of training and support, which includes: mandatory induction of approximately 50-70 hours of face-to-face training supplemented with self-directed online learning; a period of shadowing before independently supporting clients; ongoing support from an experienced mentor; and monthly supervision sessions led by a mental health professional.

Our Role

Amma holds a unique and privileged position by providing continuous support to individuals from pregnancy to the postpartum period. This continuity and depth of support means we have an intimate and first-hand view of the inequalities and challenges that individuals face during this critical phase of their lives.

In walking alongside individuals throughout the perinatal journey, we have gained a deep understanding of the issues our clients encounter, and have witnessed first-hand the systemic disparities, socio-economic challenges, and healthcare inequalities that can contribute to poor birth outcomes.

Our role is non-clinical. Nonetheless, we occupy a valuable position within the spectrum of perinatal care as specially trained observers, supporters, and advocates. We do not believe there is a singular 'right way' to give birth. Instead, our principal aim is to ensure that our clients can make and express informed decisions about their care and the care of their babies.

From the outset, we have rigorously documented comprehensive observations from both our staff and volunteer companions, as well as first-hand narratives from our clients. This has culminated in a comprehensive issues-focused depiction of the perinatal care experiences and interactions with healthcare workers for the hundreds of women we have supported over the years.

Furthermore, we feel an ethical responsibility to disseminate our findings and observations on these pertinent issues, which is a key driver in the creation of this report. This commitment is particularly poignant for refugee and asylum-seeking women, whose experiences are often marginalised and misunderstood. We recognise the discomfort this might cause for some; but it is imperative that we persist in amplifying these voices. Listening to the narratives of those with lived experiences is, after all, an integral component of the broader efforts to decolonise reproductive healthcare.

Context

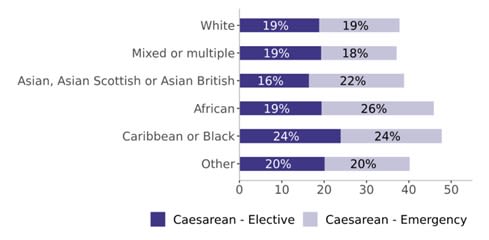

Racialised inequalities in maternal care: UK Context

Maternal health disparities in the UK reveal disturbingly elevated risks for women from minoritised backgrounds, particularly Black and Asian communities. According to MBRRACE-UK, Black women face a fourfold higher risk of maternal death during the childbearing year, while Asian women confront a twofold greater risk than their white women. Moreover, infants born to Black women exhibit significantly higher risks of stillbirth, premature birth, and neonatal death compared to those born to white women.

The 2021 MBRRACE report identifies crucial factors contributing to maternal mortality, such as heart disease, and emphasises a pervasive "constellation of biases" hindering access to necessary care. Urgent action is recommended to address multifaceted challenges, including the dismantling of racial and cultural biases.

The most recent MBRRACE-UK report scrutinises the care provided to Asian, Black, and White women whose babies experienced adverse outcomes, revealing pervasive issues of poor-quality care across all ethnic groups. The "MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Confidential Enquiry" report for 2023, updated in 2024, critically examines care disparities between Black and White women who experienced stillbirth or neonatal death.

The report identifies significant opportunities for improvement in care that could have positively impacted the outcomes for both babies and mothers. Notably, it revealed that poor quality care, including inadequate interpreting, was a contributing factor to baby deaths across all ethnic groups.

Insights into the poorest grading of care quality affecting the outcomes for both the baby and mother at different points along the care pathway are provided for each ethnic group. The report identifies challenges in recording ethnicity, nationality, and citizenship status consistently, alongside issues in addressing language needs. It highlights inconsistencies in using independent interpretation services and reveals that routine mental health questions were less likely for women from Black ethnic backgrounds. Barriers to accessing specific care were more common for women from Black ethnic backgrounds, resulting in non-compliance. Complex social risk factors were less systematically recorded for Black women, emphasising the need for more personalized and compassionate care.

Racialised inequalities in maternal care: Scottish Context

Public Health Scotland's latest report on monitoring racialised health inequalities in Scotland acknowledges that reducing racialised inequalities in maternal health is key to achieving improvements in population health. This report highlights that, in 2022, the proportion of pregnancies registered by the 12th week of gestation was lower for all ethnic minority groups compared to those of White ethnicity, where 94% registered by this point. The lowest registration rate, at 70%, was observed among individuals of African ethnicity. Additionally, the report highlights that living in more deprived areas is associated with delayed pregnancy registration. Pregnant women of African and Caribbean or Black ethnic backgrounds are more likely to reside in such deprived areas when compared to pregnant White women.

Specific challenges facing childbearing refugees and asylum-seeking individuals

In the last twenty years, a growing number of refugee and asylum-seeking individuals, particularly those from racialised backgrounds, have settled in Scotland. Refugees and asylum-seeking individuals face multiple vulnerability factors that place them at risk of loneliness and social isolation, amplifying the risk of adverse health outcomes. The intersection of refugee/asylum status, gender, and racial/ethnic identity further compounds the vulnerability of these women to experience loneliness.

Refugee and asylum-seeking women in the UK have a higher risk of perinatal mental health problems compared to the general population, holding a much higher risk of postnatal depression and other mental health concerns during the perinatal period. This can include varying psychosocial issues, including social isolation, loneliness, post-traumatic stress disorder, pre and post-migration, and depression, all of which can greatly impact mental well-being.

During this time, mothers also experience the emotional impacts of “family separation, language barriers, precarious immigration status, and unfamiliarity with a host country’s cultures”. Many are also placed in unfamiliar communities without a support system or social network to rely on, greatly compromising their health and well-being. Many experience high levels of stress, depression, and postnatal depression, which can also impact the well-being of young children and may have consequences on healthy early development.

However, the research in this area is limited. Many of the studies that examine maternal mental health amongst migrant women do not distinguish between immigrants, refugees, and people seeking asylum. These distinctions matter because they can highlight the compounding challenges faced by different populations, which can in turn affect service provision.

For many, their experiences of migration and resettlement have been marked by trauma, uncertainty, and dislocation, which can lead to heightened stress and mental health issues during pregnancy. Accessing equitable care becomes not only a matter of physical well-being but a crucial means of emotional support and stability. These barriers to care underline the necessary work of refugee supporting organisations to provide tailored, trauma informed, culturally literate, and appropriate services to this specific population.

Maternity crisis

The challenges faced by all birthing people reflects a crisis in maternity care and maternity staffing. High numbers of midwives are leaving the profession due to not being able to deliver safe care to individuals in the current system.

Findings from the 2018 WHELM study revealed high levels of anxiety, depression, work-related stress, and burnout amongst midwives in the UK. This mirrors the RCM Scottish Survey Report 2022, which focused on the significant challenges midwives in Scotland are facing, with safety, low staffing, and stress some of the biggest issues among members. The survey found three quarters had considered leaving midwifery, 41% had not been given access to statutory training during work hours, and half of respondents said their hospital or maternity unit ‘rarely’ had safe staffing levels.

A recent Care Quality Commission report focused on maternity services also highlighted the desperate need to recruit and retain more midwives, with the Royal College of Midwives framing it as a ‘wake-up call’ to the Government to urgently address years of under-investment in maternity healthcare.

The revelations brought forth in the 2022 Ockenden review and Kirkup investigation, exposing critical lapses in maternity care, cast a shadow not just on specific hospital trusts but on the entire systemic framework. Within each report, the recurring themes of uncompassionate and dehumanised care, insufficient staffing and resources, and diminished morale paint a disheartening picture. These reports demonstrate that these issues are symptomatic of deeply ingrained and interconnected issues pervasive throughout the United Kingdom.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also had far-reaching consequences, affecting Scotland, the UK, and the global landscape of health for years to come. Its impacts span various aspects of society, including the realm of birth. The Royal College of Midwives’ ‘Blueprint for Better Maternity Care in Scotland’, published in 2021, highlights that the pandemic disproportionately affected socially deprived areas, highlighting deep-rooted inequalities. The pandemic hit the most deprived communities, particularly Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups, who already face racial inequalities in healthcare.

Healthcare staff, including those in maternity services, endured significant challenges during the pandemic. Recovery for both the system and personnel is essential, with continued support for staff wellbeing and addressing long-term health impacts of COVID-19. These impacts compound the maternity crisis which was already present.

Methodology

Population Sample

This report focuses on the experiences of 100 Amma clients, 40 of whom gave birth in 2021 and 60 in 2022. These individuals were from 31 different countries, primarily spanning Africa and Asia. Interviews and testimonials also include clients who gave birth in 2023.

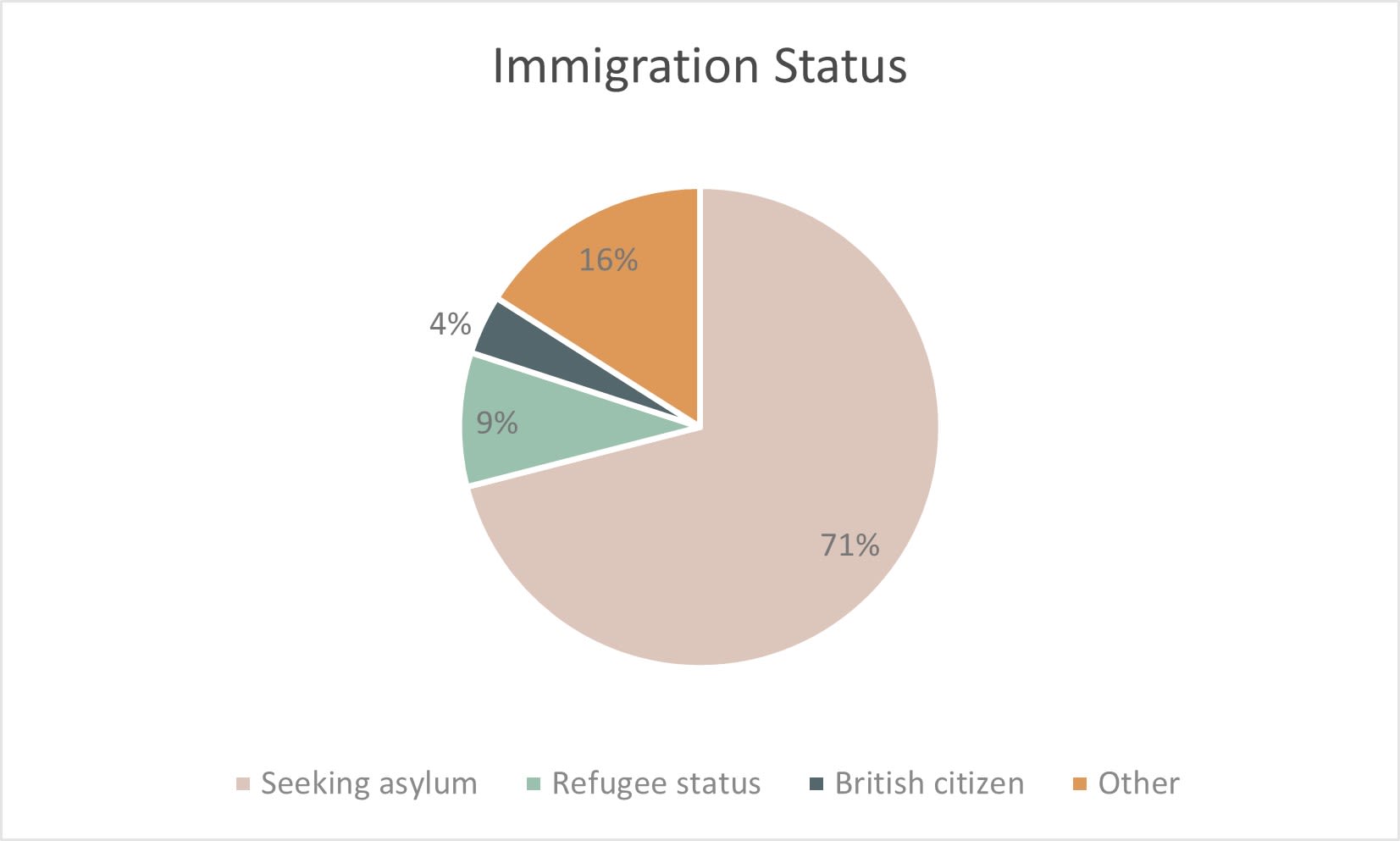

71% of individuals were in the asylum process. See Figure 1.

Figure 1

Figure 1

A mixed method approach was used to gather the evidence for this report, which included the following.

Evidence review of the challenges to equitable maternal care in Scotland

A rapid evidence review provides the wider context to ground the topics covered in this report. Sources included both grey and academic literature including Government and NHS reports, policy documents, and statistics, as well as academic journal articles. See 'Context' section for more information.

Birth Outcomes and Maternity Experiences Monitoring Reports

Following each birth we support, a monitoring report is created that captures data relating to our clients’ experiences of NHS perinatal care. For this report, monitoring reports for 100 Amma clients were analysed.

Although the sample for this report is comprised of 100 individuals, some monitoring reports lack complete information in cases where we were not present at the birth. Despite this limitation, the data we have provides valuable insights for our research objectives. We have acknowledged any incomplete data within the relevant sections of this report.

This data was recorded in our Client Record Management (CRM) system by our perinatal staff and volunteer companions. All information was recorded using a standardised reporting template that included:

- Assigned hospital

- Birth interventions and methods of delivery and reasons cited (induction/planned & unplanned caesarean sections)

- If induced, at how many weeks

- Issues with interpreter provision

- Observations of poor practice or discrimination

Our companions, trained as advocates and specialised observers, possess the ability to offer detailed observations that shed light on the diverse challenges our clients encounter. For this report, we analysed their observations relating to our population sample to gain valuable insights into our clients' perinatal care experiences.

Client Records

As part of our commitment to maintaining comprehensive records and ensuring consistent care, we utilise our CRM system for documenting necessary information. For this report, we analysed records relating to our population sample to better understand our clients' demographics and perinatal care experiences.

Semi-structured Interviews with Birthing Parents

To explore in depth the issues emerging from our birth outcomes monitoring data, six Amma clients who gave birth in the last two years were interviewed by Sarah Shemery, PhD candidate. To enable a deeper understanding of client’s situations for those we interviewed, we also reviewed their client records on our CRM.

These interviews were intended to provide a deeper understanding of the participants' experiences and are includes as individual stories within the report, with all names changed to protect privacy and confidentiality. Using semi-structured interviews allows for a comprehensive examination of the birthing process from the perspective of those who have undergone it.

Interviews enquired about people’s birthing experiences and questions centred around the following areas:

- Pregnancy support and safety

- Care and interaction with hospital staff

- Understanding and sense of control

- Communication and choices

Companion Testimonials

Two client records from 2023 were selected to further illustrate issues appearing through the analysis of the Birth Outcomes and Maternity Experiences Monitoring Reports. The Amma companions for these clients provided first-hand accounts of the birth.

Gaining the informed consent of our research participants was vital.

Certain content within this report has the potential to elicit challenging emotions, so please take care when reading. Our intention is that it inspires open and honest discussions around how to improve maternity services for both midwives and the people they care for. We aspire for the material to provoke constructive conversations and shared learning that will take us one step closer to creating a maternity system that values and protects the wellbeing of healthcare workers whilst also ensuring that all people giving birth receive equitable, person-centred care.

Practice Issues & Discrimination

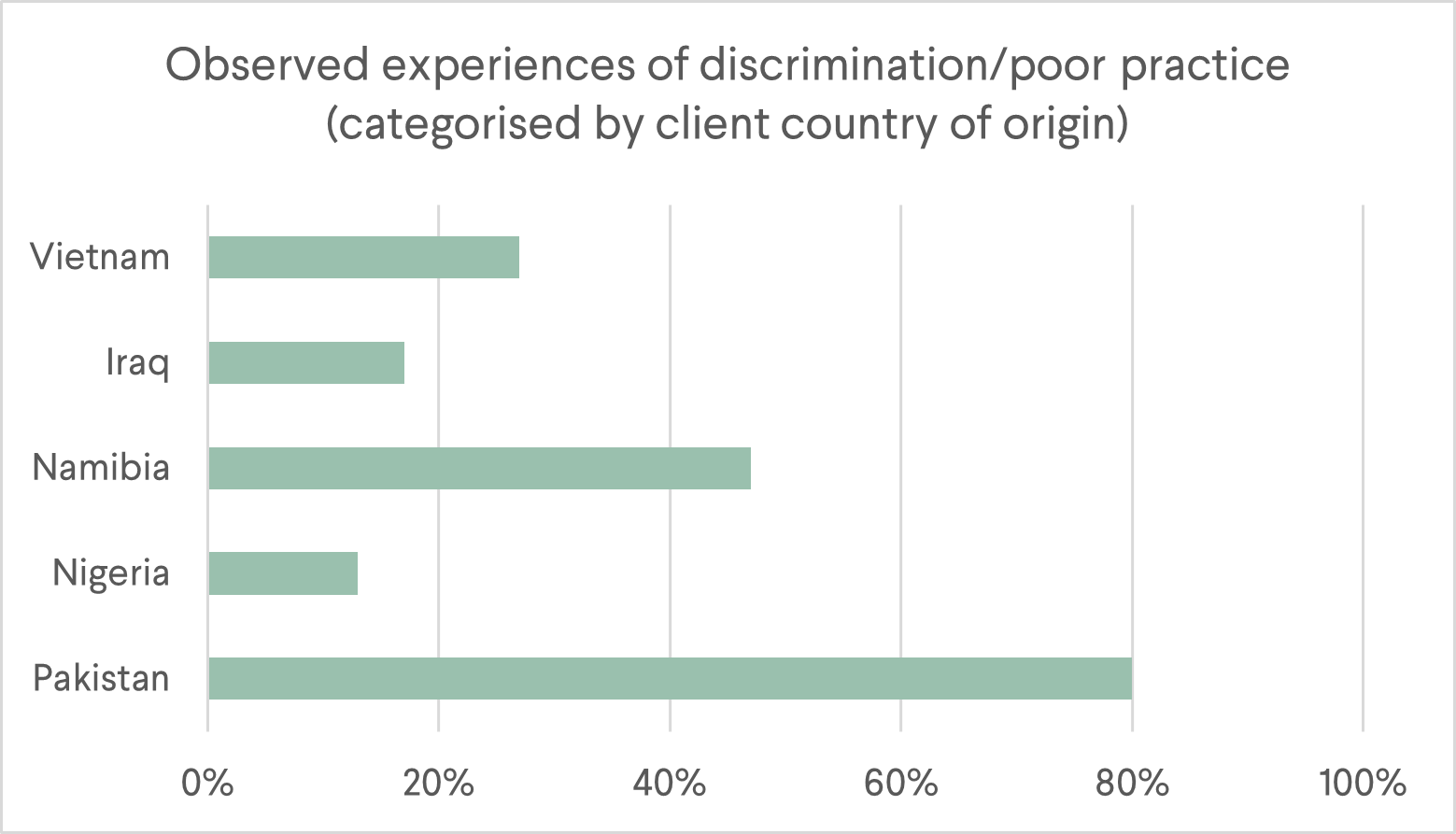

During the 2021-22 period, birth companions reportedpractice issues or discrimination affecting 37% of 76 recorded cases.

In cases where there were a small number of individuals from the same country, we attempted a comparison by country of origin (see Figure 2). It is worth noting that the sample sizes are not sufficiently large to yield significant results, although the indicative data suggests clients from Pakistan experienced disproportionately higher incidences of discrimination and/or practice issues.

Figure 2

Figure 2

The following themes were identified:

Lack of attention and delayed pain relief

There were several instances where women were not given adequate attention, or their pain seemed to be dismissed.

"I also had issues with my catheter, because at some point it moved and it wasn't in place. So, I literally slept in a wet bed all through the night. And I got a cold the next morning because when they came to check my temperature, it was high. And that was as a result of me sleeping in a wet bed. My baby cried all through the night, and I was in pain. I couldn't do anything. I was cold, and shivering and I didn't get any attention. Nobody came." (Client testimonial)

[Postnatal ward]: “At 9:00 pm they tried to get [client] to stand and walk. This took several attempts as [client] complained of feeling extremely dizzy when she stood up for the first time after surgery. Eventually [client] walked a few steps. [Client] was feeding her baby and asked for water from one of the ward staff and the staff member became upset and was rude to [client]. When the staff member came back to check on other babies on the ward, they checked every other child except for [client’s]. [Client] was refused pain medication by the same staff member and was told she would get it at "drug time". I advised [client] to report this to the sister in charge of the ward the next day, which she did.” (Companion observation)

“[Client] was experiencing a lot of back pain and was keen to stay off the bed, so I asked a midwife she could have a birth ball. An hour passed, so I asked again if [client] could have a birth ball, which never arrived. I mentioned to the midwife that [client] was now contracting regularly, but she was dismissive of this and insisted [client] proceed with the induction. We waited a while longer and eventually the midwife came to get [client] for the foley insertion. We had to walk down the hall to another ward. As [client] was walking, she was having to stop and breathe through her contractions. The midwife kept saying to [client], ‘I know it’s sore hen, that’s why I’m always telling people it’s best to stay up and moving!’, which was ironic given we had been requesting a ball for hours for that very reason. At no point had [client] ever indicated she wanted to be anything but upright.” (Companion observation)

Inadequate Consent & Communication

Instances were reported where consent was not fully obtained or respected. In some cases, medical procedures were continued despite the mother explicitly requesting them to stop. There were also concerns about inadequate explanations of procedures, such as breaking waters or using a foetal scalp monitor. Language barriers and a lack of interpreters further exacerbated communication issues.

"Midwives kept pushing [client] to try gas and air. When she eventually tried it, she said she didn't like it and didn't want to use it. But every time she had a contraction, they held it up to her and one point they were close to shoving it in her mouth. I had to grab it from the midwife and say 'No, thank you', reminding her that [client] had declined to use it."(Companion observation)

"While we were waiting for the anaesthetist to arrive and administer the epidural, the midwife handed me the card that explains all the risks and asked me to read it to [client]. I challenged her on this and insisted it would be more appropriate for her or the anaesthetist to do that. I also asked [client] whether she knew what an epidural is, and she said no — so I asked the midwife to first explain to [client] what it is before getting into the risks. The midwife wasn't doing what I asked so I had to explain not only how epidurals work but also the risks. Even when the anaesthetist arrived, they insisted I read out the risks." (Companion observation)

"During the third stage, the hormone injection was given without consent. The midwife said, 'I'm just giving you a wee injection to help deliver your placenta', which was then administered before I had a chance to say anything.’ (Companion observation)

"Following a standard clinic appointment at [hospital], the clinic midwife told her that she would be examining [client with experience of FGM] today. The midwife acknowledged that [client] had not had time to prepare herself for this examination but did not give her the option of postponing it and returning at a later date. [Client] expressed to [birth companion] that she felt unprepared for this examination but was not aware that patients had the right to decline examinations or treatments until she attended an Amma antenatal class. [Client] stated that, had she known she had the right to refuse the examination, she would have felt more comfortable arranging a subsequent appointment for the examination so that she had time to emotionally prepare herself." (Companion observation)

"Not long after [client]'s waters were broken the intensity of her pain rapidly increased. Midwives also started to express concern with the baby’s trace. A consultant was called to look at the CTG – she said the baby’s heart rate was dipping after each contraction and that, although he seemed to be recovering well, they were having difficulty picking up an accurate trace. She advised placing a ‘wee clip’ on the baby’s head.

I asked her to fully explain to [client] what she meant by a clip, because I understood this to be a small screw. The consultant said there are ‘virtually no risks’ to the baby and that it is a very safe procedure. I questioned this, as my understanding was that there were risks, and the consultant said she would return to discuss it later."

“The midwives offered [client] pain relief but she refused. They continued to offer, and she continued to refuse. The midwife then said, ‘Why don't you just have an epidural, there's no points for birthing without it!’. I stepped in and said ‘Excuse me, but she has already said no several times. Did you not hear her?’ The midwife threw her hands up in the air and said ‘Would you want to be like this? She needs pain relief!’. I said calmly that no, I would not like to be like this but that it's [client’s] decision.

The midwife then started suggesting diamorphine, telling [client] it would help her sleep. She asked several times if she would like it to help her rest and eventually [client] passively nodded. The midwife looked at me and said, ‘I think that was a yes, do you?’ I said, ‘If you're not sure then I suggest you ask again’. When [client] eventually said ‘okay’, the midwife left to get the diamorphine and I tried to explain to [client] what to expect. At this point she was in so much pain it was difficult to communicate so I'm not sure she fully understood what was happening. The diamorphine did help to calm [client] but before long she was in agony, and the midwife again started trying to convince her to get an epidural which [client] eventually agreed to.” (Companion observation)"

"[Client] called after 38-week scan saying she was being induced the next day. She was very afraid that the baby hadn't grown and there was something wrong, but she didn't have an understanding of her choices or really what the issue could be. We weren't planning to support at the birth, but I went to the hospital at the time of the planned induction. The midwife wasn't explaining her specific situation as she thought this was done already. We advocated for [client] to see a doctor to explain further." (Companion observation)

“With all examinations, [client] was advised that if she was experiencing unbearable pain she would only have to say ‘stop’ and the doctor examining her would immediately do so. This was not the case on every occasion [client] was examined. [Client] would say ‘stop’ and the doctor would continue with the procedure immediately. After noticing that the doctor had not stopped at [client’s] request, I would then repeat [client’s] request to stop vocally and using a hand to gesture ‘stop’. The doctor would stop then and apologise as well as asking permission to continue.” (Companion observation)

Restriction of choices and disregard for preferences

Companions observed women feeling discouraged from certain birth positions or place/type of birth (e.g. midwife-led unit, birthing pool). Their birth plans were sometimes interrogated, and their preferences were not always fully respected or discussed. Some companions observed clients being pressured to undergo induction or start using contraception postnatally despite expressing their preferences otherwise.

“We discussed the option of giving birth at the midwife-led unit. Midwife immediately said she didn't think that would be an option for [client] as they won't take anyone on the red pathway. I asked for clarification as to why [client] is on the red pathway. Midwife explained that [client] is considered high risk because of the past trauma she's experienced and the circumstances through which she became pregnant. She said most of their concerns are related to [client]'s mental health and ability to bond with the baby. Midwife said that if [client] hadn't experienced trauma she would be considered a very low-risk pregnancy.

I felt like this was a very one-sided discussion. [Client] struggles with English and the two midwives in the room talked at length about the benefits of giving birth at the PRM without stopping to make sure [client] was understanding. Then when they asked [client] if there's anything they could do to help her feel more at home there, [client] just shrugged and said, 'I don't know, whatever you think.'” (Companion observation)

“Midwife asked [client] about contraception. When [client] said she didn't need contraception and knows how to not get pregnant and that she isn't having sex, the midwife pointed at [client]’s belly and said, ‘apparently not’. This felt judgmental and not at all trauma-informed (especially given that I'm not sure if we know the origin of this pregnancy and if it was consensual).” (Companion observation)

“I mentioned that the midwife in theatre had said [client]’s placenta was ‘huge’. I said she had a birth plan with her and that [client] gave it to the midwife but that they didn't read it. [Client] wanted to see the placenta, which was in the plan, but was not shown to her.” (Companion observation)

Insensitive and disrespectful behaviour

Instances of disrespectful behaviour by healthcare workers were reported, including insensitive communication, discussing sensitive information within earshot of the birthing person, engaging in unrelated conversations during labour, and exhibiting micro-aggressions or racial/cultural biases. There were also reports of religious beliefs not being considered.

“During labour, the midwife asked [client] (from Malawi) if she had heard of David Livingstone — when she said she hadn't, the midwife said ‘I thought you'd have learnt about him in school! Were you off school that day?’ I found it deeply uncomfortable given the association with colonialism — and even more so because this was all happening during labour.” (Companion observation)

“I felt no respect was given to the birthing environment. When I arrived, the lights were on full blast, radio blaring in the background with high energy music, everyone chatting over [client]. Throughout the day I kept having to turn the lights off, encourage quiet voices, change the music...” (Companion observation)

“Following birth, on the postnatal ward, [client] expressed feeling ‘belittled’ when midwives spoke openly about her in front of other patients in the room. She recalls, ‘I would sometimes hear a midwife and another midwife say, ‘Oh yeah, her partner is not in the UK’, or, ‘She’s a refugee’.” (Client testimonial)

“[Client] said she didn't have a good experience with the doctor. He was very irritable and asked why she was there. She said he wasn't speaking very nicely and seemed annoyed. He said he could do a procedure during the C-section to stop her having any more children. When [client] said she didn't want this, he said they will have to organise contraception as she shouldn't have any more children.” (Companion observation)

Traumatic experiences and misinformation

Some women experienced distressing situations due to misinformation or inadequate explanations of birth processes. This led to unnecessary pressure, stress, and worry during pregnancy and birth.

“The first issue occurred when [client] first presented at maternity services. [Client] was told that ‘most people with FGM require some form of surgery’ prior to or during birth. [Client] disclosed to [birth companion] that this experience gave her some anxiety around ‘being cut again’ despite knowing that women from her family and community back home who have experienced the same form of FGM have given birth vaginally.” (Companion observation)

“When asked by [client’s] friend if baby would likely be born today, midwife responded ‘Yes, there's a time limit on this baby!’ I could tell [client] felt pressured by this, as things were progressing slowly.” (Companion observation)

Inadequate support and dismissive attitudes

There were reports of inadequate post-birth support, particularly regarding breastfeeding and concerns raised by the mothers. Some women felt that their concerns were dismissed, and they received insufficient support from staff.

“[Client] voiced concerns about the midwifery care post-birth too. She said it was mixed and some midwives were almost dismissive of her concerns about breastfeeding and being visibly very upset. My experience of the midwives in the ward after birth was that they were very dismissive of any concerns I raised about how she was getting on with breastfeeding and the level of support she was getting.” (Companion observation)

“[Client] tried breastfeeding an hour or so after birth. The midwife was supporting but wasn’t very helpful. [Client] was getting frustrated as baby wasn't opening his mouth and I tried to gently say he is learning how to do it and to have loads of skin-to-skin and get to know each other, etc. Also showed her how to express a bit of milk onto nipple. A while later midwife came back saying he needs fed ASAP because of the gestational diabetes, so she could try expressing or "just give a wee bottle for now". [Client] was exhausted and so weak she couldn't hold him anymore so went for the bottle.” (Companion observation)

Racism & Discrimination: Fatiya’s Story

Fatiya was referred to Amma in her third trimester of pregnancy. She had suffered a previous stillbirth and was experiencing a complicated pregnancy.

Fatiya delivered her second baby safely and speaks highly of the support she received during labour, which included her Amma birth companion. She says, “[The midwife] was listening if I say, ‘I don't want this’, ‘I want this’. She was a very nice lady.”

However, following birth, Fatiya says she experienced racism and discrimination on the postnatal ward, describing how isolated she felt during this time: “I was alone. Except Amma, nobody else was there with me. Even sometimes [the midwives] wouldn’t come around. When I [buzzed] the alarm, nobody came.” She recalls having to ask for her bed sheets to be changed after two days.

Fatiya says, “The next night, I needed some pads—and [the midwife] was like, “Why did you not bring some with you?” She said, “Here!” and she threw four pads at me. She said, “This is four pads. You can use them. I don’t know if it will be enough for you, but don’t ask again.” The midwife suggested Fatiya ask her husband to bring her more pads, and Fatiya had to explain her husband was not present.

Fatiya felt neglected throughout her time on the postnatal ward. She recalls, "I was sleeping and didn’t even remember I needed to change the baby’s nappy. Nobody came all night. Nobody woke me up, nobody asked me if I needed tea. Nobody even checked on me. Nobody even fed me. I called the alarm and they were like, 'We put your food down there.' I asked, 'Why did you not wake me? The food is cold.' She said, 'We don’t wake people up.' I asked her to help me show how to change the baby’s nappy. She said, 'Why didn’t you change the baby’s nappy in a long time? A whole day, all night. That’s too long.' But I didn’t know. I was so exhausted and never did this before, and I didn’t know how many times to change."

When she eventually changed the baby, Fatiya told the midwife she had forgotten to pack baby wipes. The midwife said, “Use a tissue. Wake up, go walk. We use tissue.”

Fatiya noticed a difference in how the midwives were treating her compared to the other patients, which she attributes to racism. She says, “They were being very nice to the next person. They were holding her baby, helping her change nappies. They were bringing her tea, waking her up. [Asking her] “Did you have a shower? Do you want me to bring you some towels?” But nobody was asking me.

Fatiya recalls, “One of [the midwives] told me, you are alone. Where is your husband?” I told her he was elsewhere. She said, “Why?’ You're going to struggle by yourself with the baby.”

Despite how she was feeling, Fatiya wanted to stay in hospital for as long as possible as she was anxious about returning home alone with her baby. However, she felt the midwives were eager for her to leave: “They were like, ‘You should go home. You’re fine. Your baby’s fine.’” In contrast, “They were telling other [patients], ‘Take your time! Why are you leaving so quickly?’”

“[The midwives] wanted me to go [home] because [they] were thinking I was demanding a lot of help that [they] didn’t want to offer. When I see [the midwives] being nice to [other patients] and making them feel comfortable, but [they] don’t care about me—that’s racism. Because at the end of the day, I believe we may have different colour, but we bleed the same way. We have the same emotions and we feel the same way. You know, if you get hurt, you feel pain—I feel that pain when you tell me bad words just to hurt me.”

Fatiya says it was easier to just “stay quiet” and ignore what was happening to her. She went home after one week in hospital.

Issues with Interpreting

In 2021-22, 39% of 100 clients required an interpreter. During this time period, we recorded issues with interpreting in 74% of these cases. This figure was notably higher at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (QEH), with issues reported in 85% of cases compared to 68% at Princess Royal Maternity Hospital (PRM).

Three main themes about interpreter provision were identified on the monitoring form: lack of availability of (suitable) interpreters, staff understanding and willingness to use interpreters and technical issues. Below is a summary of these issues as they were reported on Amma’s Birth Outcomes and Maternity Experiences Monitoring Reports.

Availability of interpreters

- Difficult to get a hold of interpreter

- No interpreter used in maternity assessment and again following birth when client needed stitches

- In-person interpreter requested but not available. Phone interpreter used.

- Waited two hours for an interpreter

- Midwives could not reach an interpreter during the birth. Birth companion had to use LiveLink to obtain consent for Caesarean section.

- No interpreter available with specific dialect

- Client reluctant to speak with male interpreter

- Interpreter failed to show up at appointment

- No interpreter during antenatal appointment which led to client not understanding conversations about induction and should dystocia

- No NHS interpreter available for a specific language. Staff inability/willingness to access an interpreter through other routes resulted in client not understanding serious health issues for several months interpreting.

Inadequate interpreting

- Frustrated client called her daughter to translate when male interpreter seemed disengaged

- Client believed her baby had tumours rather than cysts and thought the baby may have Down’s Syndrome. Client felt this communication was due to inadequate interpreting.

- Issues with interpreter not understanding due to wrong dialect

Staff unwillingness/inability to use an interpreter

- Interpreter used briefly to explain something and then hung up

- Amma staff needed to advocate for interpreters to be used

- Hospital reluctant to use interpreters even to deliver key medical information

- Interpreters not always used during labour

- Call handlers in maternity assessment unsure how to phone a client back with an interpreter. On more than one occasion, Amma had to explain how to use Livelink.

- Maternity assessment staff thought that they were unable to use telephone interpreters to call a client who needed to speak to them on the phone

- Midwife relied on birth companion to translate

- Repeated reminders not to rely on Google Translate for important conversations relations to interventions and/or consent

- Midwife continued to use Google Translate even when client asked for an interpreter. When birth companion intervened, midwife insisted Google Translate was fine.

- Midwife requested to use birth companions’ phone with Google Translate and said this is what would normally be used for interpreting.

- Staff assumed that because client had conversational English they would not need an interpreter.

Technical issues

- Phone kept cutting off

- Poor sound

- Faulty service

- The connection was bad despite trying several times

- NHS phone battery was low and needed to hang up to recharge

- Very difficult with signal/line to interpreter; many requests to repeat, interpreter suggested calling someone else several times due to connection being so poor.

- Lack of written translated resources

Key observations from companions about interpreter issues which illustrate the issues identified above include:

“At times it was difficult to get the hospital staff to use interpreters and key medical information was going to be delivered to the client without a translator until I intervened.” (Companion observation)

“Midwife gestured and shouted in English whenever the interpreter wasn’t available. She also insisted certain information had been shared with the client via the interpreter (e.g., dilation amount), but companion heard the conversation in English and knew this to be untrue. Midwife did not give client the opportunity to ask questions whilst interpreter was on the line; birth companion had to advocate for this during a subsequent call.” (Companion observation)

“Called maternity assessment and asked midwife to call back with interpreter. Midwife advised she didn't know how. I talked her through LiveLink instructions. She called back to say she had spoken to [client] and thanked me for teaching her how to use the phone interpreter.” (Companion observation)

“On antenatal ward, [client] asked for interpreter and the midwife got her to type into her phone on Google Translate, even though she was clearly in pain and distress. I asked her to get the interpreter on the phone and she said, ‘This has been working fine.’” (Companion observation)

“On arrival in the labour ward, baby was coming fast. I asked them to get an interpreter, and they said they would, but in the meantime, I used LiveLink on my phone because there was no time to wait.” (Companion observation)

“Later in the birth, the hospital found it hard to get hold of a telephone interpreter and I had to provide one using my phone, when preparing, getting consent, and going into theatre.” (Companion observation)

“[Client] said she had problems with interpreters in the past. When she had called in the past, she said she had asked for them to call back with an interpreter and no one had called. She said she had been reluctant to turn up at the hospital as she would have to wait for around three hours for an interpreter. She asked the midwife to clarify what she was told at her last scan two days previously. The midwife explained that the baby has two cysts — one on the bladder and one on the bowel. They don't seem to be problematic. They would like to keep scanning her in pregnancy to see whether they grow. [Client] said that she had been very upset as the previous interpreter had said these were tumours rather than cysts.” (Companion observation)

"When I arrived at the hospital, I was surprised to learn that [client] had already left with a man. This was especially worrying given [client]'s history of trafficking. On top of this, no interpreter was used to discuss the discharge paperwork with [client]. I urged the midwife to call [client] to check that she was safe. She didn't use an interpreter, so I insisted that she phone back with an interpreter. Thankfully, [client] was able to confirm that she was home safe, but the incident raised red flags regarding the discharge process and communication." (Companion observation)

Interpreter Issues: Kadija’s Story

Kadija was referred to Amma in the second trimester of her pregnancy. Kadija speaks and understands limited English and is unable to read in any language. At the time, the NHS interpreting service was experiencing a shortage of interpreters who spoke Kadija’s language, but there were interpreters available through other companies.

Kadija experienced a high-risk pregnancy due to concerns over her baby’s growth, so had to attend frequent antenatal appointments. During these appointments, Kadija did not have access to an interpreter.

She says, “The [medical staff] said that they were trying to get interpreters, but they were unable to find. There was a time when they said they were a bit worried as well, because my stomach was too small—the baby was too small.”

Kadija explains, “It was really difficult, because there were so many things I wanted to ask. I wanted to know what was going on—I wanted to ask but there was no interpreter.”

At around 30 weeks, Kadija became severely unwell, and an emergency Caesarean section was required. As a result, she never had the opportunity to ask the questions that had arisen during her pregnancy. She explains, “I had an early delivery, an early birth. I had the baby and then couldn’t ask any more questions”.

The complexity of both Kadija's health condition and her baby’s premature birth led to an extended hospital stay, where Kadija and her baby were in separate wards for a period of time. Throughout her care, Kadija stated that no interpreters were provided—despite repeated requests from her Amma companions, who were advocating on her behalf.

On one occasion, when both Kadija and her baby were still in hospital, an Amma birth companion attended a cross-departmental meeting to discuss Kadija's condition and care plan. An interpreter was requested, and Kadija was advised that a telephone interpreter had been booked. During the meeting, NHS staff made several attempts to call the interpreter, but an error on the booking system meant this did not happen. Kadija had no choice but to call a friend to interpret over the phone to allow the meeting to progress.

At the time, Kadija explained to her Amma birth companion that she had very little understanding of her overall diagnosis or the long-term implications of her condition. She was also unsure about her baby’s health or any long-term impacts. As a consequence, her mental health was directly impacted.

“The first major problem [whilst in the hospital] was I wasn't given the use of an interpreter, and it was very difficult. That stressed me a lot. An interpreter was not given—and when medication was given to me, I didn't have an interpreter to explain to me how to take the medication. And then when Amma would come and visit me in the hospital they would ask me, ‘Did you have an interpreter?’ And I would say no. And then they were confused as well, because I was in hospital for a long time. I was very confused. There were lots of things going in my mind. I wondered 'What is happening to me?' I didn't understand anything.”

Despite the significant issues with interpreting, Kadija felt well cared for whilst in hospital. She mentions one member of staff, in particular: “[She] used to come to encourage me. Sometimes she would come find me crying and she would just encourage me, [saying] “Things will be better, you will be okay.”

Lan speaks no English. She speaks a common language.

Lan's story highlights the negative impact of inadequate interpretation and reluctance to use interpreters. It raises questions about what might have happened without us advocating for an interpreter, and whether Lan would have been able to understand information about her care and provide informed consent.

This case study was created using detailed observations provided by Lan’s birth companions.

Lan’s Story: Companion’s Perspective

I accompanied Lan to her elective Caesarean section as an Amma birth companion.

When Lan was given a bed, I alerted the midwife that Lan would need an interpreter. The midwife asked if I had arranged one. I advised that this would need to be arranged by the hospital.

When Lan was taken for pre-op tests, the midwife started to ask questions without an interpreter. Again, I explained that an interpreter was needed. A telephone interpreter was eventually provided.

Throughout this conversation, it became apparent that Lan had already had her pre-op appointment the previous evening despite there being no obvious record of this having been done. The confusion surrounding this, coupled with the lack of adequate interpreting, meant that Lan had not eaten since the previous day, which caused her to experience low blood sugar.

Eventually, Lan and I were taken to a ward to wait for her Caesarean section. I informed the midwives that an interpreter was needed. With no interpreter present, the midwife carried out blood pressure and blood sugar checks and asked Lan about allergies and any previous operations. They also asked about consent to give the baby vitamin K following birth. Again, I reiterated that they would need to wait for the interpreter to arrive to have this conversation.

After more than four hours from my arrival at the hospital, an interpreter arrived. My understanding was that not having an interpreter pre-booked delayed the process.

Unfortunately, even with an interpreter present, there were several issues with communication. The interpreter would routinely fail to interpret what the client or medical staff were saying, needing to be prompted to pass things on. Other times, it was clear that she was interpreting to Lan based on her own predictions of what the medical staff were going to say rather than what had been said. She also interjected with her own individual opinions at inappropriate times. It was clear that the doctor felt frustrated, having to assertively stipulate what was expected of the interpreter.

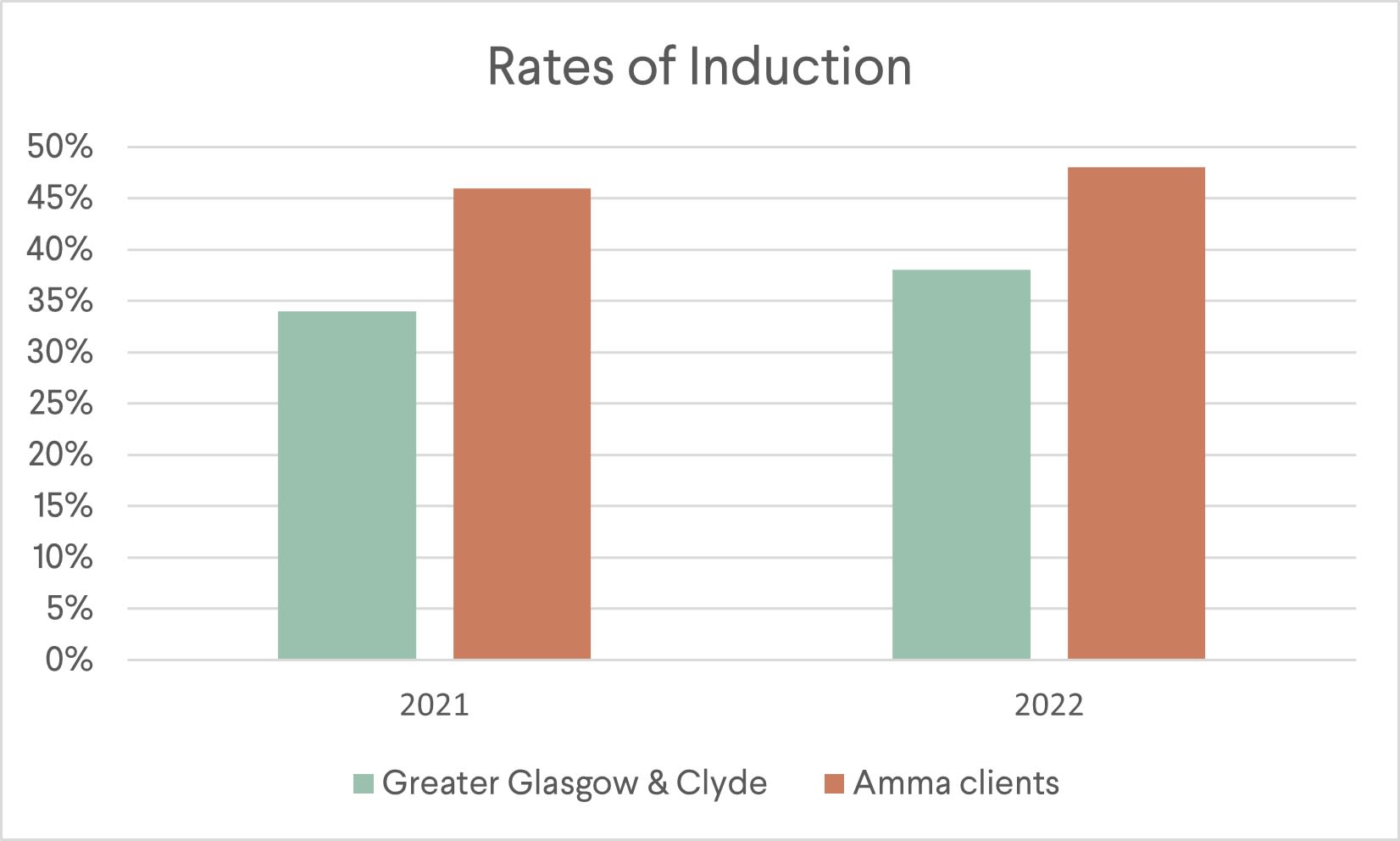

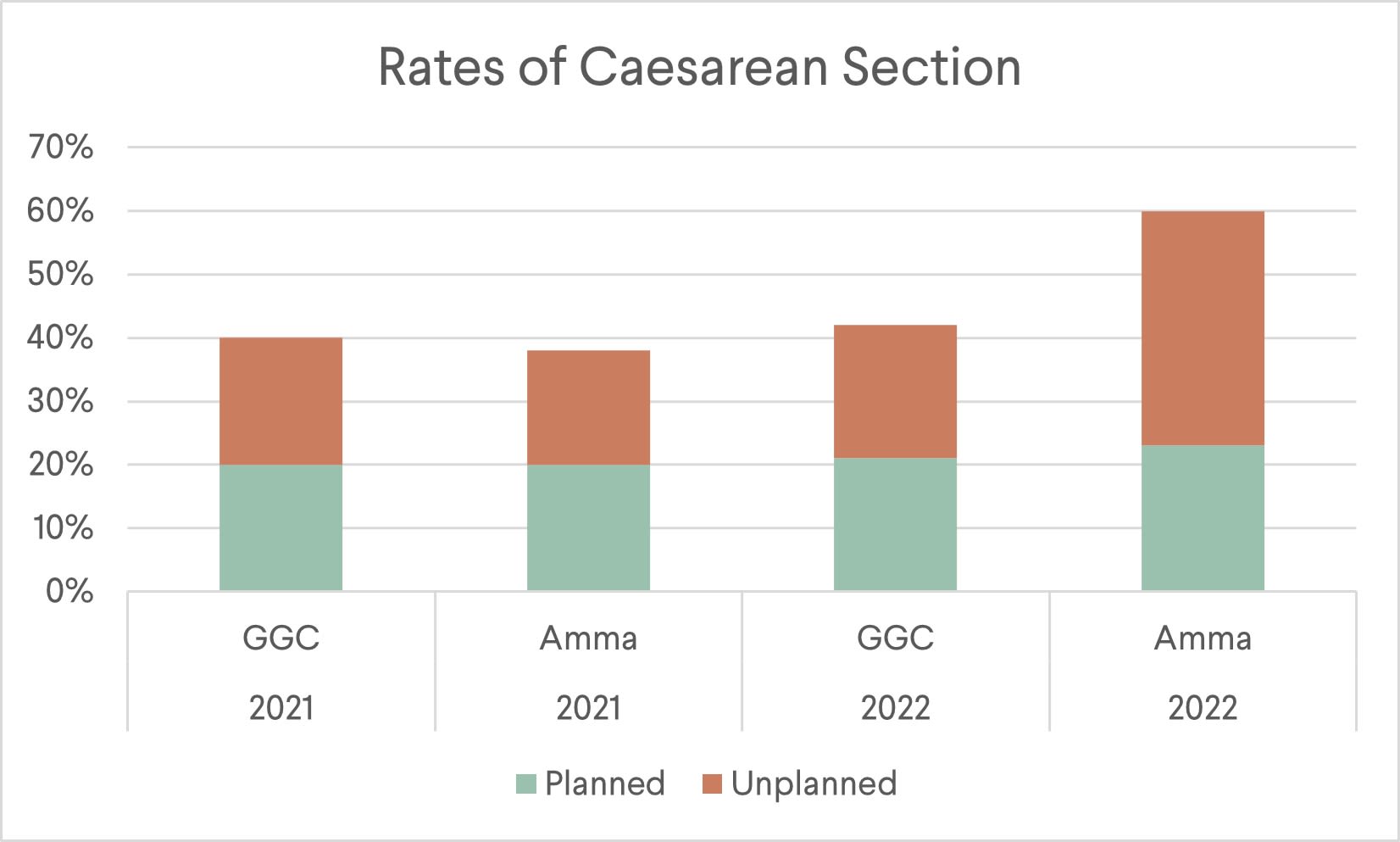

Rates of Induction

The trend across NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde shows an increase in induction rates between 2021-2022, which our data also reflects. However, it is important to note that our data reveals an average induction rate that is 11 percentage points higher than the figures reported for NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde in both 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 3).

In 2021, 46% of clients were induced. This rose to 48% in 2022.

The average gestational age at the time of induction was 38 + 5 weeks.

Figure 3

Figure 3

40% of the individuals who were induced gave birth by unplanned Caesarean section

Several common reasons for induction were identified, including concerns about foetal movements, decreased baby growth, gestational diabetes, post-dates, and previous stillbirths.

Although it is not our place to dispute clinical recommendations, the following observations, reported by birth companions, reflect the complex dynamics involved in decision-making around induction—including the balance between patient autonomy and medical recommendations, the impact of effective communication, and the emotional toll of these discussions on pregnant individuals. The themes also highlight the importance of addressing language barriers and ensuring that individuals fully understand the information provided to make informed choices about their care.

Fear and Anxiety

Anxiety and fear are common themes throughout our companions’ observations. Many mothers expressed anxiety about the health of the baby, the induction process, and the potential outcomes. The uncertainty surrounding the need for induction and the associated risks contributed to the emotional burden experienced by the mothers.

Some individuals expressed fear of induction due to concerns about the increased medical interventions and potential complications associated with the process. In some cases, these fears were associated with previous birth experiences or experiences that were shared by others. Some individuals worried about the perceived loss of control over the natural course of labour, fearing that induced labour may be more intense or lead to a cascade of medical interventions.

"Called [client] after her clinic appointment this morning. There were concerns over reduced growth and reduced movements and they want [client] to have induction today. [Client] doesn't want this but is worried as they've told her she has to, and they are concerned about the baby. They checked the baby's heartbeat which was fine. [Client] told [birth companion] that she was afraid of being induced, and that a friend had advised her not to get an induction. [Client] had asked the doctor to be booked in for a C-section instead. [Client] was told that would not be available for another two weeks so was not an option. I told [client] it's her right to ask for a C-section if that's what she really wants.” (Companion observation)

“Midwife asked [client] how she is feeling. [Client] replied that she is worried about being booked in for induction at this appointment and her baby being born before they are ready.” (Companion observation)

“I [birth companion] had a quick call with [client] and chatted about her antenatal appointment last week. [Client] told me that the midwife is saying her bump hasn't grown at all and if baby continues to be the same size this week then they will book her in for an induction. I asked how she is feeling about that and she said a bit worried, but also said ‘I have no choice’”. (Companion observation)

Consent and Autonomy

Observations reveal instances where mothers expressed concerns about the lack of information or incomplete explanations regarding induction procedures and associated risks. In some cases, there was a perceived need for better communication between healthcare workers and mothers, ensuring that they fully understood the reasons for induction and its potential consequences.

Testimonials also highlighted instances where pregnant individuals expressed preferences regarding induction. While some were open to the process, others expressed hesitations, concerns, or a desire to wait for a more natural onset of labour.

“They have recommended induction because of the increased risk of infection due to premature rupture of membranes. We [client and birth companion] were confused, as before they had said they did not want to induce because of the risk of uterine rupture. But we spoke to the midwife, and she said it was about a 1% chance and they would go extra slow with Syntocinon drip.” (Companion observation)

“The midwife said, ‘The plan is to break your waters once the antibiotics have finished and at the same time set up a Syntocinon drip to get your labour moving’. I interrupted her and asked, ‘Is this the plan? Has [client] given consent? She had wanted a water birth, but does this mean that's definitely not an option? Are there alternatives? Anything else we can do with positions or anything to get the labour moving?’ The midwife said we can try and see where we are and check in again in half an hour." (Companion observation)

“[Client] was offered a sweep because of her pelvic pain and discomfort during pregnancy. She declined as she is not ready. She was not told about the potential risks of a sweep and was not informed that it was a form of induction. She wants a natural birth and does not want an induction or morphine pain relief as she had bad experiences with them last time." (Companion observation)

“Visited [client] at home. We talked about induction and the different stages involved, and also that it may take days — she had thought she would definitely meet her baby on Wednesday [the date of her induction]. She really doesn't want the drip, or a C-section.” (Companion observation)

Lack of Alternative Options

Many mothers expressed preferences for a physiological birth and a desire to avoid interventions such as induction. There were several instances where mothers enquired about alternative methods to encourage physiological birth before considering induction, especially amongst those who had experienced spontaneous labour previously. However, some healthcare workers seemed reluctant to consider alternative approaches to induction.

“When [client] said she would like to push the induction to next week to try and get labour started naturally, the consultant said, ‘How are you planning to do that? Because I can tell you right now studies show none of those methods work.’” (Companion observation)

“This [client] has gestational diabetes and is being told the baby is big and she should have induction. She was told about the risk of shoulder dystocia and nerve damage and there was a discussion about the induction process. She previously had three home births in [home country] with no complications, all relatively short labours of less than 24 hours. She had no pain relief except paracetamol and movement and, although they weren't weighed at birth, she reports that all of her babies were ‘big’. [Client] didn't feel that she wants or needs induction but said she had four doctors telling her all the risks. When asked if she would like us to accompany her for her next appointment, she immediately said ‘yes, please.’” (Companion observation)

“When we arrived on the labour ward, I explained to the midwife [client]’s desire for a natural birth in the pool. I asked if it would be possible to stop the induction process, since [client] was now contracting strongly and regularly and see how things progress naturally. The midwife was very uncomfortable with the idea of halting the induction and said it is not advisable to come off the induction pathway once started but said she would speak to the midwife in charge.

When she returned, she said the best she could offer was to give [client] two hours with no additional interventions – she would then check dilation and assess whether to continue with the induction process. I knew that two hours wouldn’t be nearly enough to allow labour to progress naturally, but [client] agreed to this. The midwife made it clear that a water birth simply wouldn’t be possible because of gestational diabetes and the need to be monitored. I asked whether we could use the wireless monitors and she said they aren’t waterproof (which I have since found out is untrue).

At the end of the two hours, the midwife explained that she would like to examine [client] to see if any further dilation had occurred. If not, the next step would be to break [client]’s waters. If [client] refused this, she would potentially be moved back to maternity assessment or possibly home to labour there. [Client] agreed to the vaginal examination. Unsurprisingly, she had not dilated any further. [Client] agreed to have her waters broken.” (Companion observation)

Communication Barriers and Language Issues

Testimonials indicate instances where pregnant individuals face challenges due to language barriers, difficulties reading English, or feeling confused about the information provided. This underscores the importance of effective communication, clear explanations, and the need for interpreters or support to ensure understanding.

“When [client] came out of appointment she was a little shaken and confused and had been given information leaflets about induction (she does not read English). She was unsure of why they were discussing induction — something about the baby not growing much in the last week, but movement etc. is all fine and normal. Scan booked on Friday which she has asked me to attend." (Companion observation)

“Had to remind [midwives] multiple times to not rely on Google Translate. [Client] believed induction process had already started when it hadn't because of miscommunication.” (Companion observation)

Coercion and Pressure to Induce

Some testimonials suggest situations where there was perceived pressure or pushiness from healthcare professionals regarding induction. In some cases, pregnant individuals expressed preferences for waiting or exploring alternatives, but inductions were strongly advised.

Several testimonials also highlight instances where healthcare workers use strong language, emphasising potential catastrophic outcomes, such as stillbirth, to convey the importance of induction. The line between providing information and instilling fear is a significant theme in these testimonials.

“She explained that even if [client] didn't have gestational diabetes, she would be advising induction because of the slowed growth. Although the consultant said a lot of the right things, e.g. ultimately it's [client]'s decision and she needs to make an informed choice, I felt her language and approach was extremely coercive. For example:

- When asked about the risks of waiting to go into labour naturally, she said the risk was "small" but potentially "catastrophic" and could result in [client]’s baby dying

- When asked whether the induction could be pushed a few days, she said ‘If it's a choice between waiting a few extra days and having a baby die, I know what I would recommend.’

- When asked to quantify the risks, she said she ‘couldn't put a number on it’ but that 1 in 1000 babies born in Glasgow are stillborn, so ‘add a bit on to that’ for gestational diabetes and ‘add a bit more’ for tailed growth

- She could offer additional monitoring as an alternative to induction but said a baby could appear well one day and become very unwell or die the next, so there's no guarantees even with monitoring. I asked her to pause as it was clear [client] was getting very upset, and she said ‘I'm not trying to scare you, but I can't as an obstetrician look at this and not make you aware of the risk of stillbirth’

- She used the word ‘stillbirth’ at least 10 times and kept reiterating the risk of death

[Client] was made to feel terrified and is now incredibly anxious about her baby's health. [Client] agreed to a sweep (the doctor said membrane sweeps are not part of the induction process).” (Companion observation)

Gestational Diabetes & Baby’s Size as a Factor

Gestational diabetes and estimated size of baby (both big or small) is mentioned as a significant factor influencing the decision to induce. Many pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes had to navigate discussions about the risks associated with a larger baby, potential complications during birth, and the recommendations for induction.

"Just before we left, the midwife told [client] (via LiveLink) that as the baby is ‘on the big side’, they would get her back in for an appointment to discuss next steps (induction). I asked about this, as the sonographer had said the baby was a 'normal' size. Midwife said that the baby is tracking okay—i.e. no unusual growth—but that it had always been on the big side." (Companion observation)

“Doctor came to have a chat and went over their only concern: big baby. She was very brief and just she thinks it would be a good idea for [client with gestational diabetes] to accept a membrane sweep next week. [Client] didn't seem keen but said she'll think about it. Midwife mentioned that a sweep is really low risk and could help [client] avoid induction. Doctor came in but just explained that everyone between 41 and 42 weeks are offered induction so they want [client] to seriously consider it next week." (Companion observation)

“[Client with gestational diabetes] has been told she won’t likely be 'allowed' to go full term. She's having regular growth scans. Had gestational diabetes with first pregnancy and baby was average size. Consultant said she would not recommend a homebirth and that in fact she was advising an induction by the end of the week. Said that all women with gestational diabetes are offered induction at 38 weeks as per hospital policy.” (Companion observation)

“[Client] has been told her baby is measuring big and will be booked in for induction, without further explanation. Once we went through this process in detail, [client] is now hoping to say no to the induction and let the baby come when she's ready. [At her next appointment], the doctor was explaining that with ‘bigger babies’ there is a risk of a more traumatic birth for mum and baby, risk of shoulder dystocia, having to use instruments and the baby outgrowing the placenta. [Client] expressed she prefers to wait and see, but the doctor said the plan is for the midwife to visit [client] at home next week for her check-up, including a vaginal examination to see how the cervix is, and then book her in for induction around 39 weeks. [Client] talked about the appointment, disbelief at how things are presented and that she really prefers to let her baby decide when to come, as long as everything is fine.” (Companion observation)

Issues with Induction: Ada’s Story

Ada was referred to Amma in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She had recently been diagnosed with gestational diabetes, which was diet-controlled, and was told her baby was measuring big. An induction had been offered at 38 weeks.

When Ada first met her Amma birth companion, she stated her preference for a spontaneous, physiological birth. However, she was feeling worried because the medical staff had advised that, due to the baby’s size, her baby could get ‘stuck’ during delivery, which could cause complications.

At her 38-week appointment, Ada was again offered an induction within the coming days. Ada declined and instead opted to wait until 39 weeks. On the day of her induction, Ada presented to hospital already experiencing contractions and showing signs of labour. The induction proceeded with a Prostin gel pessary, which led to intense pain and little relief between contractions. Ada recalls:

“By the time I got to the hospital [for my induction], I'd already started having contractions—mild ones—but at the end of the day I was still induced. I don't know why, but then they still did that. After the induction, I felt neglected because I was having very intense [pain] and my contractions were coming in very heavy. I know I reached out to the midwives a couple of times. I felt like they should have moved me to the labour ward, but then I just felt like I was neglected at some point. I didn't know why I was [not on a labour ward] for that long.”

After seven hours, Ada was moved to the labour ward where she requested an epidural. The epidural was ineffective, and another one was administered, which was also ineffective. When the baby started showing signs of distress, Ada was taken into theatre for a crash Caesarean section. Ada was saddened by the outcome of her birth. She explains:

“When I had the baby, she wasn't an overweight baby—she wasn’t a big baby. She was just normal for the number of weeks she was at then. But I was given the impression she was big. They had to induce me, and that was not what I wanted, but [I did it] because they instilled this fear of having a big baby and having difficulties in pushing. It was sad that I had to go through all of that, and then she was just the right size. I had a Caesarean section, so it made me sad. If they had let me run my focus, I would've had the vaginal birth that I always wanted to have.”

Ada questions whether things would have been different had she not been induced. She says, “If I wasn't misinformed about the weight of the baby before the whole induction, I shouldn't have even gotten to that point.”

The first night following birth, Ada was in a lot of pain and was unable to pick up her baby. For several hours, she buzzed for help with no response. Eventually it was revealed the buzzer was faulty. Her catheter had also come loose and she woke up in a urine-soaked bed, shivering and unable to call for help. She explains:

“I remember I buzzed a number of times because my baby woke up and was crying, needing to be fed, and I couldn't reach out to her. I was in pain. So, I kept buzzing and nobody came all through the night. And then I also had issues with my catheter, because at some point it moved and it wasn't in place. So, I literally slept in a wet bed all through the night. And I got a cold the next morning because when they came to check my temperature, it was high. And that was as a result of me sleeping in a wet bed. My baby cried all through the night, and I was in pain. I couldn't do anything. I was cold, and shivering and I didn't get any attention. Nobody came.

And there was a time someone came because there were other mothers in the room. So someone buzzed and one of the midwives or the nurses came in, and I called out to her, but I don't know—she didn't hear me because when she attended to whoever buzzed then she just left and I didn't get any attention. I really felt sad because I couldn't attend to my baby. I was in pain, and I felt very helpless.”

Min's Story: Companion's Perspective

Upon referral to Amma, Min was experiencing significant emotional struggles, fatigue, and isolation. The traumatic circumstances surrounding her asylum-seeking journey, history of trafficking, and the lack of a support network intensified her vulnerability.

This case study delves into the issues and concerns surrounding Min's experiences, emphasising the complexities arising from her traumatic past, asylum-seeking status, and cultural differences.

This case study is an amalgamation of observations provided by Min’s birth companions.

I started supporting Min in the later stages of her pregnancy, when concerns were raised by maternity services about the size of her baby. This led to discussions about a potential induction.

When Min attended a midwife appointment during week 36 of her pregnancy, she was booked in for an induction at 37 weeks. Min expressed worry about the induction but was told by the midwife to ‘trust the doctors’. I suggested that she take the time needed to carefully consider her options and advised that she could follow up with her midwife about any unaddressed concerns.